February 2026

Welcome to my next edu-blog post. In this post I explore the recent Education White Paper, formative assessment, the wisdom of Mary Myatt and consultation release of Keeping Children Safe in Education 2026. All essential reads for those in school leadership. Oh, and I also reflect on the importance of kindness in leadership.

Every Child Achieving and Thriving

Published on 23 February 2026, the Government’s schools White Paper sets out a long-term vision for education in England up to the 2030s, emphasising inclusion, high standards and redesigned school support structures.

Core aims and commitments include:

1. Raising attainment and closing gaps

- A national ambition that pupils leave school with improved qualifications — e.g., an average GCSE grade 5 or higher across the system.

- A specific goal to halve the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers.

2. Transforming inclusion and SEND support

- A major reform of the special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) system, moving toward new tiers of support — Individual Support Plans and Specialist Provision Packages.

- Only the most complex needs would retain legally enforceable Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs), while others receive statutory support plans locally in mainstream schools.

- A £3.8–£4 billion investment to boost SEND provision, train teachers and expand specialist capacity.

3. Broadening the school experience

- A push from “narrow to broad”: enhancing enrichment, arts, citizenship, oracy and digital learning alongside core literacy and numeracy.

- Schools encouraged to embed arts and other creative experiences more deeply.

4. Teacher workforce and leadership

- Plans include targeted incentives to recruit and retain teachers, especially in schools that face recruitment challenges.

- A strategic plan for 6,500 additional teachers is set out alongside the White Paper.

5. Stronger engagement and attendance

- A renewed focus on raising attendance levels and pupil engagement, with expectations for schools to monitor and act on belonging and participation.

6. System structure and accountability

- Encouragement — and in some areas expectation — for schools to work in stronger collaborations, including trusts which can support improvement and inclusion at scale.

- Changes to admissions and exclusions policy are also under consideration to further fairness and reduce off-rolling.

So What Happens Next? Policy vs Implementation

White Papers in the UK are policy proposals and intentions, not legislation. They influence future bills, regulations or statutory guidance — but they do not themselves change the law. Any statutory reforms to SEND, curriculum, assessments or trust governance will require new legislation or regulation that Parliament must pass.

What this means for schools:

✔ Immediate planning and consultation responses are expected

✔ Existing law (e.g., current SEND Code of Practice, accountability frameworks) remains in force until any new legislation passes

✔ Some proposals — particularly structural or statutory changes — may take several years to implement

What This Means for School Leaders and Governors?

- Respond to the consultation: Many reforms invite formal responses from schools, families and trusts.

- Plan for inclusion, not just compliance: The focus on inclusion benchmarks and engagement could shape inspections and accountability.

- Watch legislative developments: School policy, accountability and SEN frameworks may shift significantly once the consultation closes and legislation is drafted.

Formative Assessment

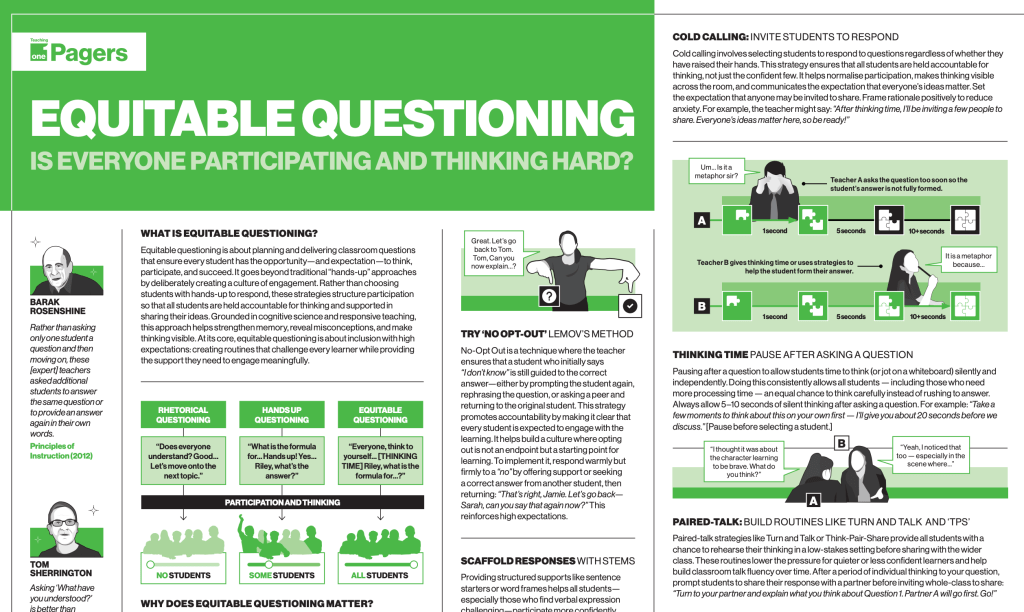

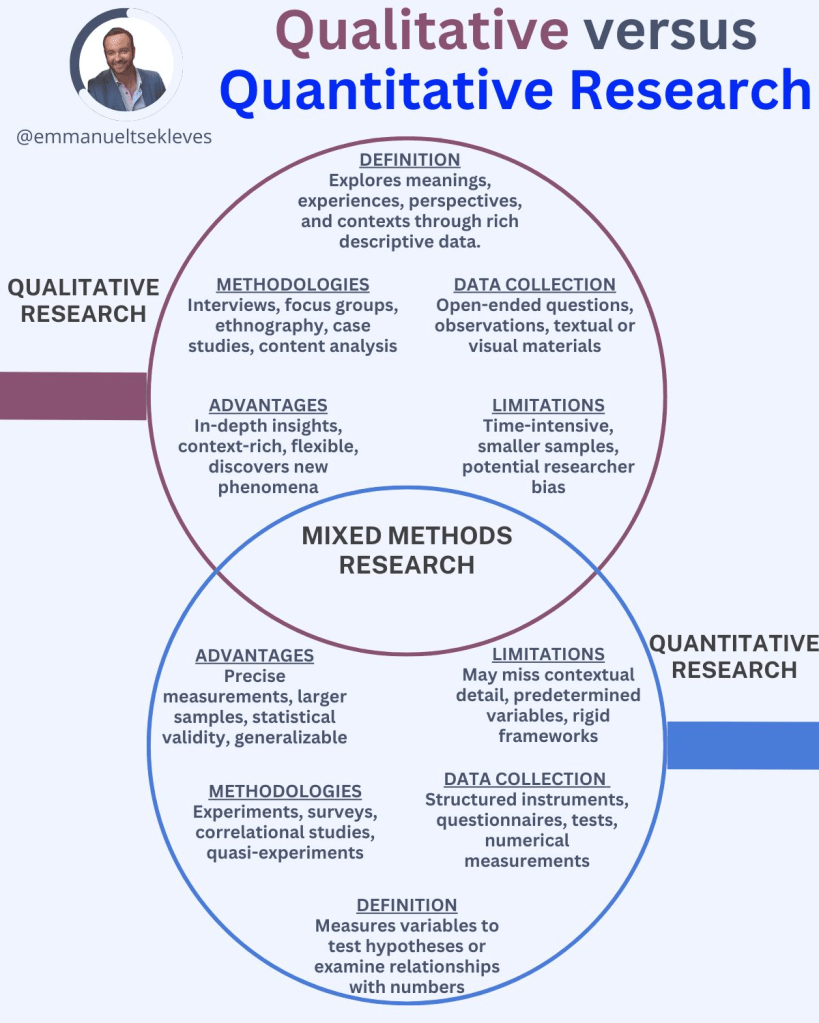

Formative assessment doesn’t fail because the idea is wrong. It fails because the implementation is weak. Kate Jones writes about the importance of getting formative assessment right in a recent blog post A summary of evidence based formative assessment strategies.

Dylan Wiliam defined it simply:

Use evidence in real time to modify teaching and learning.

Not marking. Not data walls. Not coloured pens. Real-time adjustment. Yet in many schools it becomes:

• Exit tickets with no follow-up

• Tick-box success criteria

• Peer feedback scripts

• Heavy marking policies

The strategy survives. The impact disappears.

The EEF’s implementation guidance explains why.

Change sticks only when:

🔹 Teachers are genuinely engaged

🔹 The approach fits the context

🔹 Leaders move through Explore → Prepare → Deliver → Sustain

Most schools jump straight to “Deliver.” No exploration. No shared understanding. No sustained support. We then call it inconsistency.

If you want formative assessment to work, stop asking: “Are teachers doing it?”

Start asking:

“Is teaching changing because of it?”

“Are misconceptions surfacing earlier?”

“Can pupils explain what quality looks like?”

Formative assessment isn’t a strategy.

It’s disciplined professional craft — sustained through intelligent implementation.

Completed work is not learning – the wisdom of Mary Myatt

Mary Myatt recently published a LinkedIn post on this issue and it is worthy of a read. As always, Mary grounds us in common educational sense, she reminds us that completed work is not the same as learning. For those who are not on LinkedIn (seriously, where have you been since the fall of Twitter?) her sis her post:

I’ve sat with pupils, talking about what they’ve been learning, their books full of neat handwriting and ticked boxes.

“Can you tell me something interesting that you’ve learned about recently?” I say.

Too often, the response is “I don’t really remember.”

The work was done, but the learning hadn’t stuck.

This is what happens too often when we offer tasks that keep children busy, worksheets that get finished, but where there’s no real thinking underneath.

We praise completion because it’s visible. It feels like progress, but completion without understanding is an illusion.

What should leaders look for instead?

👉 Can pupils explain what they’ve learned in their own words, not just read back what they wrote?

👉 Are there opportunties to build in talk before writing? As James Britton said “Writing floats on a sea of talk.” Without discussion, pupils have fewer ideas to commit to paper.

👉 Is there evidence of thinking, or just evidence of finishing?

When we talk with pupils, what they can, and can’t tell us, reveals everything.

KCSIE 2026

Take a look at this helpful synopsis from Nicole and consultation for 2026 KCSIE. Some important changes are afoot. 👇

The DfE has launched the KCSIE 2026 consultation, with significant proposals affecting every school, trust, and college. Here are the headlines you need to know:

🔹 Part One – Safeguarding for All Staff

• Removal of Annex A – all staff must now read full Part One

• Alignment with Working Together

• New Early Help indicators (e.g., repeated removals, part‑time timetables)

• Clearer legal definitions of rape and sexual assault

• Recognition that CSE victims may be criminalised through coercion

• Expanded guidance on serious youth violence

• Earlier expectation to consider LADO referrals

🔹 Part Two – Management of Safeguarding

Mental Health: Clearer guidance on when concerns become safeguarding issues

Gender Questioning: Integrated advice; legal duties on single‑sex spaces & sports

Technical updates:

• Racism & derogatory behaviour in preventative education

• New AI safeguarding guidance

• Annual filtering & monitoring reviews

• Cybersecurity recognised as a safeguarding issue

• Stronger expectations for AP, medical needs, SEND barriers

• Improved information‑sharing, including DSL‑to‑DSL handovers

🔹 Part Three – Safer Recruitment

• New SCR template

• Clearer rules preventing unnecessary DBS checks for work experience

🔹 Part Four – Allegations

• Trainee teachers explicitly included in all allegations processes

• Safeguarding responsibility confirmed for all individuals on site

🔹 Part Five – Child‑on‑Child Abuse

Revised structure aligned with the Hackett Continuum, clarifying:

1️⃣ Early HSB → 2️⃣ Sexual harassment → 3️⃣ Sexual violence

🔹 Annex Updates

• Guidance on AI‑generated child abuse material & Financially motivated sexual extortion (FMSE)

• Stronger expectations on DSL cover and required skills & experience

🔹 Evidence Base Development

Views sought on: affluent neglect, AI risks, BSL version of KCSIE, Children affected by Domestic Abuse (CADA), grooming gangs, gaming platforms, sextortion, non‑criminal HSB, staff self‑referral, Teenage relationship abuse (TRA), verbal abuse, and DSL workload.

📢 Have your say

These proposals will shape safeguarding practice for years to come.

Every voice matters: DSLs, teachers, governors, leaders, safeguarding partners, alternative provision providers, and social care colleagues.

👉 Access the full consultation here:

https://lnkd.in/eh3Nh6qE

I provide safeguarding audits for schools. This involves a two day on-site review with a full actionable report. Get in touch if you would like to talk this through.

Kindness in leadership

Kindness. Not the fluffy, laminated-on-the-wall kind. The disciplined, deliberate, courageous kind.

In school leadership, kindness is often misunderstood. It is not avoiding difficult conversations. It is not lowering standards. And it certainly isn’t trying to be liked.

Kindness is clarity delivered with care.

In a climate of sharper accountability, rising parental expectation and increasing staff pressure, the temptation is to harden. To become transactional. To manage by spreadsheet.

Here’s what I’ve learned working with headteachers, trust leaders and middle leaders:

Kindness is a leadership strategy.

It looks like:

• Pausing before responding to an email that raises your blood pressure

• Asking, “What’s happening for you?” instead of “Why hasn’t this been done?”

• Giving precise feedback without stripping someone of dignity

• Holding the line on expectations while holding people steady

Kindness creates psychological safety.

And psychological safety creates performance.

Staff who feel respected:

✔ take more risks in their teaching

✔ admit mistakes earlier

✔ engage more honestly in professional dialogue

✔ stay longer

In other words — kindness improves outcomes.

But here’s the twist.

Kind leadership is often harder than directive leadership.

It requires:

• Emotional regulation

• Deep listening

• Moral courage

• Consistency under pressure

It means having the uncomfortable conversation — but doing it in a way that says, “I believe in you enough to be honest.”

The schools I see thriving right now aren’t the loudest or the most performative. They are the ones where leaders are steady, humane and intentional. In a sector under strain, kindness isn’t weakness. It’s resilience in action.

And perhaps the uncomfortable question for us as leaders is this:

When the pressure rises, do people experience more of our authority — or more of our humanity?

Above all – in leadership, be kind.

And finally…

If you would like me to work with you then do get in touch. We can have a coffee and a chat. The graphic below shares some of the ways that school and trust leaders have used me in the past year. As always, happy to engage in bespoke work that suits your needs.

For those who have undertaken my professional training programme for subject leaders and senior leaders in the past, you may be interested in my updated programme that aligns to the new 2025 Ofsted Inspection Framework. This will empower your subject leaders to attune their practice to the inspection framework while strengthening their own professional knowledge and impact on pupil outcomes.