The affirming power of research

Staff in a busy school can appear to race along the landscape like a startled herd of gazelles darting every which way as the educational landscape changes; swiftly changing direction as the needs of their children change, as the leadership of the school evolves, as each framework from Ofsted is introduced, as each new curriculum test forms new challenges for our most vulnerable pupils, as the government introduce another white paper; I could go on.

Evidence based practice allows us as professionals to stop for a moment, to look around at the landscape beneath us, to enjoy its beauty, to learn from those around us and to deepen our understanding of what truly works in education. Is it possible in the midst of such educational flux for evidence based practice to give teachers and schools a renewed authority to create their own destiny and to provide an individualised environment in which teachers and pupils thrive?

Creating space for research

The key to engaging school staff in evidence based practice is to ensure there is a time when the noise of every day life in school is stilled. While we continue with our myriad of roles and responsibilities in school our mind is filled with stuff to do. Evidence based practice forms when we still this noise and spend time reading and researching, take time to deeply reflect on our own practice, ask challenging questions and engage in deep observations that allow us to reflect on what truly works in education. As a school leader, I am also acutely aware I need to make time for myself to be reflective as well as my staff in order for research to take place.

After reflecting on the impact of the year’s staff training, I looked at the impact of the training days in particular. Although the days provided valuable time for staff to be together to discuss practice and learn key skills; their impact appeared more beneficial for specific groups rather than the whole staff. In order to create space for my staff, I had to take something away; I therefore used three training days, equating to fifteen hours of research time for each teacher across the school. The days were placed at the end of the school year but the teachers were charged with accruing fifteen hours of research across the year to equate with the three training days given. The pay back, was to ask each teacher to publish or present their findings formally through a research paper, leading a staff meeting, writing a blog or presenting at a Teach Meet.

Formal Research Networks

In order to provide rigour to our evidence based practice, we joined the South East Region Cambridge Primary Review Trust as a partner school. The CPRT, led by Vanessa Young from Canterbury Christ Church University gathers together research-active schools to share practice and link with other schools and research bodies nationally. This group provided our school with a powerful model of research based on the key priorities of the CPRT.

As a group of eleven primary schools in our collaboration, we developed a more formal understanding of research based practice with Canterbury Christ Church University. Teachers from the nine schools met across the year to learn about research methodology and were given an opportunity to put the methodology into practice in an action research project. The outcomes of the research projects were then published by the university and a celebration event held to share the outcomes of the research projects. The research empowered staff to deepen their pedagogical understanding and share their new learning with colleagues.

Using Appraisal to Develop a Culture of Evidence Based Practice

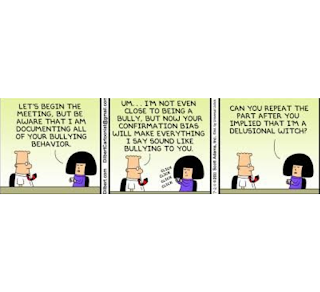

Appraisal offers a powerful tool with which to target evidence based practice. We trained senior staff as Mentor-Coaches and used the principles of Mentor-Coaching and appreciative enquiry to allow the teachers to devise a research based target that would develop their practice and enhance pupil’s learning. Appraisal discussions led to a range of exciting and meaningful targets that encouraged teachers to develop their research based practice. Research based targets were varied and included research on the impact of parents on early reading, use of Google Docs to enhance learning and the impact of Twitter on professional development. Some amazing blogs have been produced by both teaching and non-teaching staff across the school, many have been re-tweeted by +ukedchat .

The Learning Ticket

I gave each teacher a ‘Learning Ticket’, each ticket had a cash value of £150 and was to be spent on their research based appraisal target. In addition to the Learning Ticket, three Research Bursaries were made available for teachers to bid for. Each Research Bursary had a cash value of £500 and teachers could bid collectively for these to enhance their research. One teacher bid for a research bursary to research into the impact of Lego in story writing while another undertook an international research project into the teaching of phonics in the USA, Japan and Finland.

Blue Sky

We adopted a digital appraisal and CPD tracking system called Blue Sky. This system allowed appraisers to input appraisal targets, link them to the school key priorities and track each staff members’ appraisal and training activity. Once trained, staff were able to upload appraisal evidence, CPD courses and their impact and upload relevant evidence linked to their appraisal targets. The programme also allowed staff to track their research time while their reviewer was able to give a gentle nudge to staff who had been less than active over a period of time. As a result, appraisal reviews became truly owned by each member of staff and there were no surprises at the end of the appraisal cycle as there had been a regular conversation through the Blue Sky program between appraisee and appraiser throughout the year.

Teach Meets

With an evidence based appraisal target in place for each teacher and Blue Sky tracking progress towards the targets, teachers developed a variety of new practice based on the research undertaken. We needed a forum to share this practice and celebrate the success across the school and beyond school. We therefore used the Teach Meet model to provide a platform for the research outcomes for staff. The Teach Meet is a meeting of teachers to share their practice in short ‘micro-presentations’. Each presentation at our teach meet lasted no longer than seven minutes. Our first Teach Meet focussed on ‘Irresistible Writing” and the second on ‘Irresistible Learning’ and shared a range of practice across the school that was a result of the research based practice in appraisal. The Teach Meet has been an exciting and engaging way of celebrating success of research based practice and sharing practice that makes a positive difference to children’s learning. Teach Meets have also encouraged the sharing of practice across schools locally and beyond.

Where to now?

Working in a school and multi academy trust that has a evidence based practice embedded in it’s pedagogy is a real thrill. Engaging with the CPRT has allowed our staff to deepen the rigour and effectiveness of their research and has led us as a school to develop a culture of evidence based practice that helps engage our staff, raise standards for our pupils and draw high quality staff to our appointments. The CPRT has now ended its tenure as a research body and handed the flame on to the Chartered College for Teaching who will act as custodian of all CPRT research. We will now lead on with the principles that underpinned the CPRT as we move this research network forward with the CCoT.

If we are to create an exciting and engaging education system, we must continue to ask questions that encourage us to gently push boundaries and give us the conviction to create our own path into the horizon. By providing our staff with the space to engage in evidence based research in our exponentially busy life within school, the benefits to our school, our staff and our children are palpable. Allowing us to stop for a moment, look around and breathe before creating our path ahead.

Enjoy the journey!